Leaving Kalinchok

- Abigail Weeks

- Jun 27, 2018

- 5 min read

Updated: Sep 9, 2018

Today was our last morning in Kalinchok.

I woke up with the significance of our departure weighing a bit heavily on my mind. I am so grateful for the opportunity to spend five weeks in this community.

While I have traveled before, I have not been so lucky to stay for more than a month and become privy to the daily routines of my adopted neighbors, acquainted with familiar faces, and accustomed to a new way of life, as I have been in Kalinchok.

I found it so bizarre that all at once, I am able to simply pack up my bags, and leave. How can a place of such permanence, where generation have cultivated the same terraces and used the same cobbled paths, be so transient in my life?

Now in Charikot, with slightly acrid air and constant traffic, I am wistful for the mornings I woke up in a hammock with the clouds not yet obstructing the jagged mountain ranges.

I enjoyed the "rustic" amenities that meant taking bucket showers, using pit latrines, hand-washing laundry, walking up steep paths, eating food that came mostly from just a few terraces away, and admiring quaint tin homes.

There's definitely a Thoreau-esque romantic simplicity to my time in Kalinchok. But how easy it is for me, as a privileged Coloradan, to abandon this lifestyle on a whim as soon as our construction project is over.

It can be easy to overlook the reality of this community simply because I was gifted the leisurely aspects of it.

Water quality here (as I can provide data for) is poor. While I was able to pump and steri-pen my water, Kalinchok remains without any sort of water purification system. The result is water rife with coliforms.

The intricate terraces of corn and potatoes form a scenic shot. However, agriculture takes up most of community members' time, and is incredibly demanding. Lack of diversified crops leads to poor nutrition and health problems.

Our pit latrine was kept clean, but not all community members have such nice amenities nor the training for proper sanitation management.

Small homes dotting the hills and people bustling up the hill carrying wood created cause for practice Nepali conversations, yet the reality is that most homes I saw were intended as mere temporary structures. All buildings in Kalinchok were destroyed in the 2015 earthquake and now, even three years later, people are at still at work rebuilding their homes.

While each day brought along with it a new insight, a few moments stand out to me as particularly potent.

Two weeks ago, up at the school site, a bit above the classroom buildings, a group of women had been working to dig out a large flat area.

We spoke with a woman and found that they were from just down the hill. They needed supplemental income as she did not have a large farm so was working as a manual laborer. It was then that I noticed she was pregnant. A bit incredulous as I thought she was at least 45, I asked (politely) her age. She was 30. Manual labor had aged her. I looked more closely at the other women working, 2 other Didi's (older sisters) were also pregnant, holding shovels, and digging up the earth with bare feet.

I discussed for a long time with Bhupal cultural attitudes about family planning (the lack of which means women can be pregnant almost every year), and the role of women in this community. Many men in Kalinchok go to cities or to India to earn money. Meanwhile women tend the Kheti (crops), herd animals, all while caring for their children. Once I learned that many men work outside of Kalinchok, it became obvious to me that the majority of people I met on the path, carrying baskets of wheat and grass, walking the terraces, and walking behind their water buffalo, were Amas and Bajus (Mothers and Grandmothers), not fathers or uncles. I was left with a distinct appreciation for Kalinchok women's formidable resolve.

In two particular instances, I was struck by the desire of individuals to improve their community.

Ramdash, is a 16-year-old studying at Balodaya school. He is living with his older sister's (Janaki’s) family. We ate Dhal Baat in the morning at Janaki's tea shop when we had construction to do. Ramdash is part of the school's Eco-club. He lead a clean-up of the school grounds and was part of the anti-alcohol skit a few weeks ago. He spoke to Emily and me about what he thought needed to be done in Nepal. Ramdash explained that it was difficult for many people to get a good education here, gesturing to the tin roof of the school and expressing that during rainstorms water leaks through the roof and the patter makes it impossible to hear the teacher. He was very interested to hear what we were studying in the U.S. and asked lots about what college was like. He expressed that even with a good education, he would not be able to find a good paying job in Nepal and he wanted to study Korean so that he could get a work permit to work in Korea as a factory worker of some kind. Ramdash talked more about improvements he wanted to see at the school and about his view of Nepal.

A second instance was in the beginning of this trip. Bhupal and I were in Ward 4 testing water when a farmer came over to learn about what we were doing. Bhupal explained the importance of good water quality and also the purpose of drone mapping (questions about the drone were a common community inquiry). The man began to talk about how much Kalinchok farmers needed more agricultural training. He wanted to know how to more efficiently raise crops (such as what kind and when to plant), and how to grow food that would be healthy for his family and also make money when sold outside of Kalinchok. His emotions were strong, clear, and moving.

There are many ways the lives of people in Kalinchok can improve, and I firmly believe the best path is the one people in Kalinchok choose for themselves. "Community Development" work, is above all, a partnership.

I have been inspired by the work NCDC is doing in Kalinchok, with Water Sanitation Hygiene programs, Agricultural trainings, and working with Women's groups. I am proud to be a part of a team working with this community for the foreseeable future.

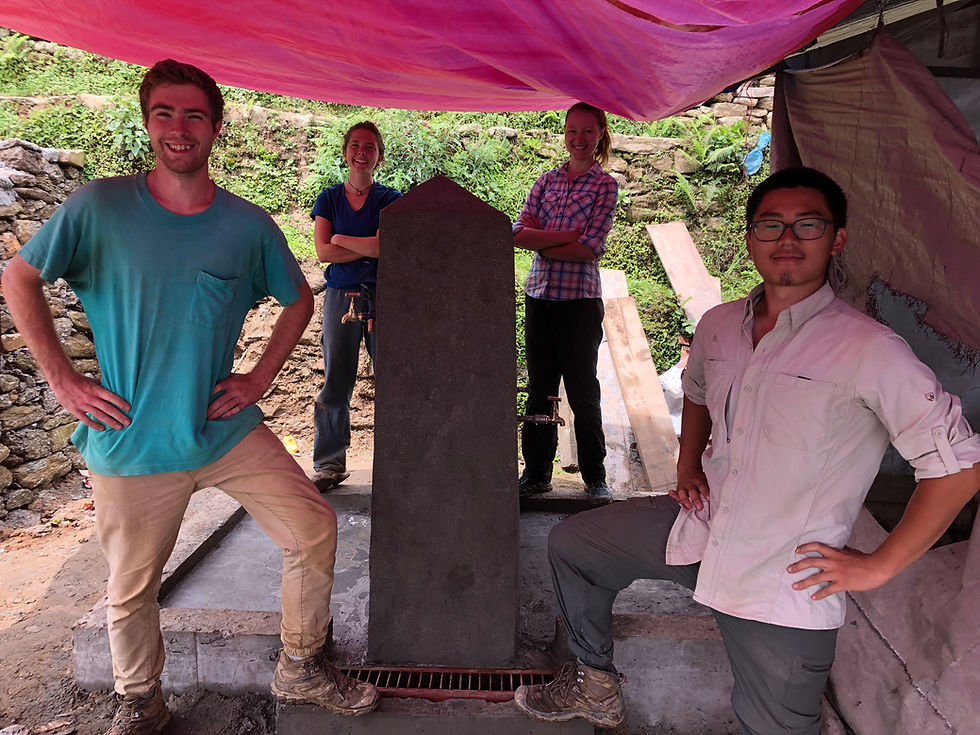

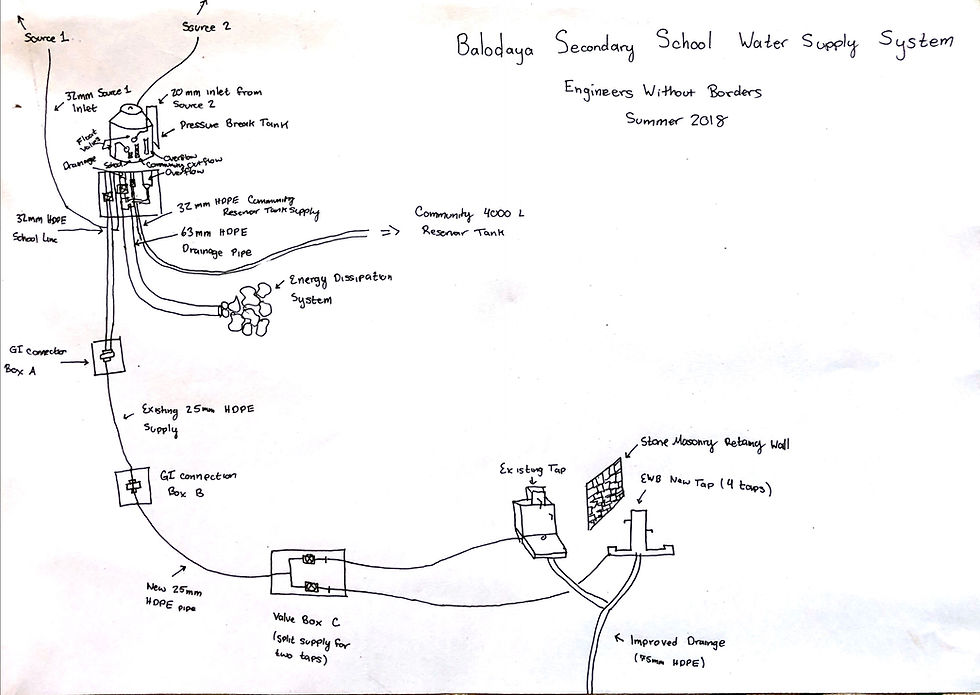

This summer we took one step towards increasing health in this community. Increased water access means hands get clean, latrines can be flushed, clothes are done, dishes get thoroughly washed, and community members can have flowing water for crops, drinking, and bathing.

As we move forward in our engineering work, we will keep in mind valuable lessons learned in logistics of supply purchasing, hiring labor, design assessment, and collaboration between many parties.

I am so grateful for the generosity in time and spirit of the Kalinchok community, including our homestay family, school teachers and administration, health post staff, and individuals we interacted with on my walks to other wards and around the school. We are blessed with the partnership with Namsaling community development center and our amazing mentor Bhupal, staff member Pradeep, technician Rajan, and permanent Kalinchok staff Nabin. Our U.S. mentor Lisa, our other mentors, and the EWB team back home have done and will continue to do all that makes implementation possible.

As an engineering student, I cannot adequately express how meaningful it is to both pursue my degree and actualize change based my education. I believe we all have a responsibility to utilize technology and resources to empower communities to meet their basic human needs, sustainably and reliably. I thank EWB and the University of Colorado for this experience.

Our work in Nepal is not yet over. We will soon be meeting with some NGO's in Kathmandu and planning supply purchases for next trip.

Thank you for reading!

Most Sincerely,

Abigail Weeks

Comments